Spring is basically here. The wind might be too strong. Julius Caesar was ambushed March 15. Everyone might care about March Madness (except you). March 17 is strangely about leprechauns, but you don’t know why (yet). Well, what matters to us in March is Women’s History. We’re going to take you along for a windy ride this month to introduce you to notable women of the past and present throughout the month.

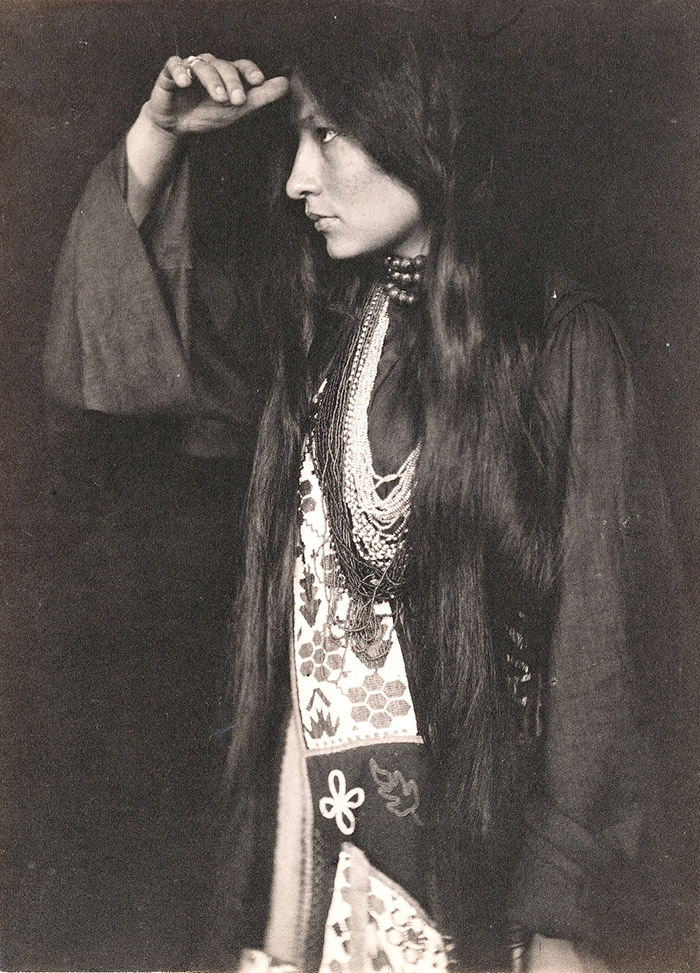

Let me kick it off with Zitkála-Šá. She was a notable Native American woman who championed for policy changes and legislation that would allow Native Americans to become citizens in their own country. She also wrote the first Native American opera. Did you know that Google commemorated the Zitkála-Šá Yankton Dakota activist with a Google Doodle last month? Zitkála-Šá was many things in her life: editor, translator, educator, musician and political activist.

To start, Zitkála-Šá’s Christian name was Gertrude Simmons Bonnin. Gertrude’s father (who was white) left the family when his daughter was a couple of years old, and their mother raised Gertrude and her older brother with their culture and tribal values. At the behest of church missionaries, Gertrude’s mother sent both of her children faraway to Indian school. It was a life-changing experience that included a high degree of assimilation efforts by the school to convert the Native children to Christianity and make students forget their tribal traditions by raising them away from their families and cultures. The school forced Gertrude to get a hair cut and began teaching her English and religion as soon as possible.

Gertrude rarely, if ever, came home for family visits. In fact, her first visit home actually took place a few years after she first boarded the train to school.

Gertrude, while experimenting with her newfound and self-aware independence in her early adulthood, decided she wanted to reclaim her identity. Gertrude decided to go by “Zitkála-Šá,” which means “Red Bird” in the Yankton Sioux language. Feeling disenfranchised, she channeled her frustrations into writing as she continued her education.

As a student, Zitkála-Šá appeared to be born with an aptitude for excelling in writing, teaching, public speaking, music, and politics. She won prizes for giving speeches. She trained in violin at the New England Conservatory of Music and later performed for President William McKinley. She joined a teacher’s college. She submitted her politically charged essays to magazines. Zitkála-Šá, when she was charged up, was controversial among school administrators, who considered her to be more or less a rabble rouser who sought to bite the hand that fed her, for speaking out against the systematic assimilation carried out by institutions like the Carlisle Indian School, where Zitkála-Šá was working as a music teacher.

Zitkála-Šá soon married and had a son. She had moved to Utah, where she became the first Native American to write an opera, The Sun Dance, which was based on some of her essays.

Soon enough, Zitkála-Šá became politically active with the Society of American Indians, who sought change for Indigenous people everywhere. She had experience working at the Bureau of Indian Affairs, so her policy work was essentially cut out for her and she held a position as the Society’s Secretary. She became a magazine editor for the Society and a traveling advocate for Native suffrage, citizenship, education, economics, health, and religion.

Tirelessly, Zitkála-Šá and the Society set upon planning for appeals to legislation to change how Native Americans fared in society. She had a notable fellow activist in her midst, Marie Louise Bottineau Baldwin, who agreed with Zitkála-Šá’s views. Each of them were bolstered by the other’s views on Indigenous society. Both felt it was possible and preferable to allow tribal citizens to keep their identities and land and allowing them the right to citizenship and voting. Her critical thinking skills and her essays helped her organize committees dedicated to passing the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 and the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934. Zitkála-Šá’s writing continued to influence Indigenous-centered policy and legislation in the years following these pivotal federal-level decisions.

Resources

I hope you learned a thing or two about Zitkála-Šá. She is one of many Indigenous faces who continues to inspire many tribal people everywhere. You can use this short, three-minute video of Zitkála-Šá for Grades 1-6.

This PBS video resource is more for your 7th and 8th graders who think cartoons are corny. It’s an in-depth look at Zitkála-Šá’s Indigenous political activism.