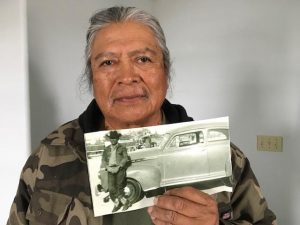

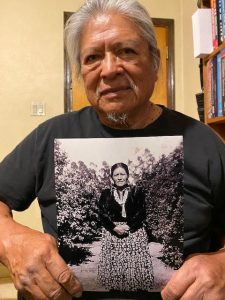

My father, Jerry Hanson, worked for Kerr-McGee in Church Rock, New Mexico from September 1978 to October or December of 1982. Four years. During that time, he earned more than enough money to build our family home in Tohatchi, New Mexico. Now, the toxic legacy of uranium mining is being shared nationwide, but sometimes there is a silver lining to all of that, and those are the “war stories,” as my dad likes to call them. “I’m a part of history,” he said, as he stood up to head to bed, as we had ended conversation for the night.

Uranium mining is a part of Navajo Nation history. We will be including it as part of our upcoming educational math game, Making Camp Navajo, which will be released this fall.

Uranium fever

Work was fun. I was a pillar miner. (Your uncle too.) The money was good, around fifteen to thirty-five dollars an hour, back when minimum wage was two dollars an hour. It really spoiled me. After they release you, and you try to get another job, you don’t feel like working for jobs that pay you pennies.

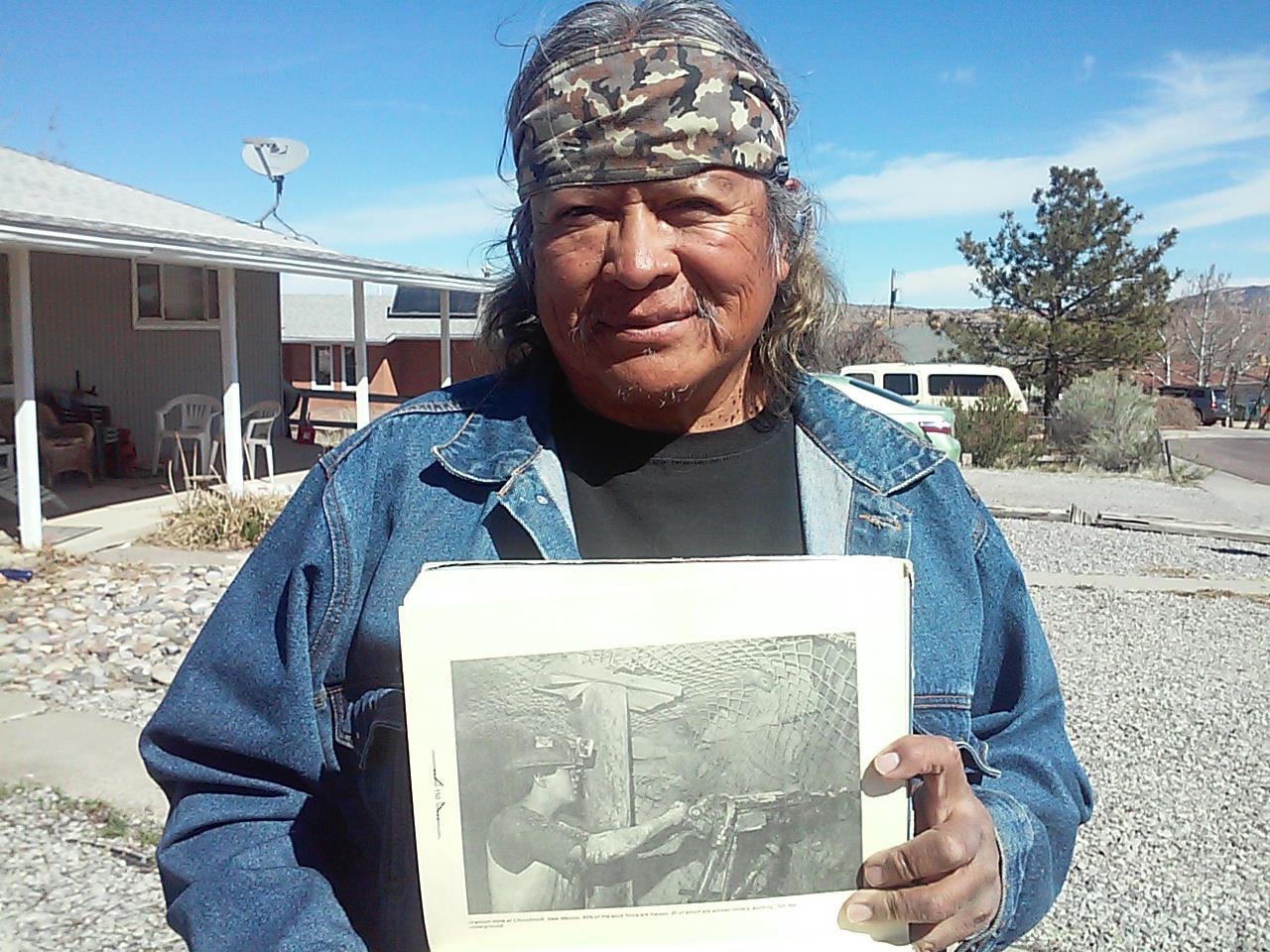

All the mining was done by hand. It wasn’t like the old days where you used a pick. We used drilling machines and explosives. Drilling machines have air hoses that shoot compressed air. There is also a water hose. The drill bit has water that shoots out at the end to lubricate the drill so it doesn’t get stuck in the rock. The roof jack keeps the ceiling from caving in. After the ore is extracted, more holes are drilled into the wall. Explosives are inserted. Each one has a timer. You want the center explosive to go off first, then the outer ones. A bucket on a cable slushes out the ore inside. The drill weighed a little over a hundred pounds. When you’re young that’s nothing.

Workwear

You just wear regular clothes. Safety glasses, helmets and ear plugs are used as protection. The machinery is so loud. You also wear a rubber suit, like coveralls, and we wore a rubber rain jacket. It’s really wet. Those places are wet from drilling using water hoses. When you stop the drilling, you put the throttle all the way back. It stops the water, but the air keeps going so the holes can be cleared for explosives. You are constantly exposed to water and mud. At the end of the day you are soaked in dust, mud, and sweat. You have to shower before you go home. You cannot go home like that. You will expose your family to ore dust at home. Leave everything at the mine. What happens at the mine stays there.

Radon

I was once exposed to radon gas. They transferred me to the surface and then the ventilation team for three months. Ventilation team tests the air quality. They measure the levels of oxygen, radon gas. We worked in a clean area. They put me in a position where we had to probe sections of the mine. They would drill at many different angles into the mining shaft. They do this to examine the body of ore in the ground. Inspectors examine the amount of ore from these tests. The data is collected and examined to trace the uranium veins. After that, they use the data to inform the miners where to drill for ore inside the mine. I worked with Edith Hood and Herbert Muskett from Mexican Springs. Another guy too, who was half-Mexican and half-Navajo. I kind of forget names.

Mining buddies

I had work friends there at the mine. Sometimes I see them around Gallup. I don’t know if some of them passed away from the virus. There was a man who was wearing a cowboy hat. Ten gallon one. He was walking around all stooped over. You know that jack I was talking about? They nicknamed him “Roof Jack” because he was leaning against the wall as if holding up the wall. We called another man “Gooseneck” because of his long neck. Gooseneck was a pipe at work that had a ninety-degree bend.

Bill Silversmith, a boss with advice

Uranium mining helped build our house. The lumber was inexpensive at the time. The house was finished after six or seven years because the electricity, water, and sewer had to be installed. So, one day, my boss and I talked for two hours during a long break. He had a lot of war stories. He got serious. He said, “You guys make a lot of money? Are you ready for living with the in-laws? Are you staying with somebody? Your friends? People always say, I’m going home, but they may not have a real home themselves. That’s not going home. You better build a house. Then you can say I’m going home.” That’s when I think ahead. I said, “I’m going to build me a house.”

Our neighbor Chee Nez, I used to work with him in construction. I asked him to build me a foundation. I hired him. We dug the foundation trench. We started building the foundation. We built the floors. Gradually, it built up. We finished the outside, the roof. He helped me out with the sheet rock and the floors. I picked it up from there. I did that. I knew a lot of carpentry already. I had delays. How am I going to dig the trench for the sewer 300 feet? I went to heavy equipment school in Provo, Utah. I went there in spring 1985. I stayed up there for the whole year. I took classes in carpentry at UNM Gallup. I took plumbing. I studied that. I did research and got ready. When I was ready, I rented a backhoe to start digging and installed that sewer line. The NTUA* inspected it, then once we got the water hooked up, we got stuck with the bills forever!

The electricity was hard. The first guy I hired did some electrical work on the house, but I didn’t like it. I took out his wires and modified it. I asked my cousin, Nathaniel Tsosie, a certified electrician. I bought what he needed and he installed it for me. Again, the NTUA inspected it. They said it was fine. The lights came on. From there it was history.

I did this for the future. If I had a family, I wanted to make sure we had rooms for the kids. So that was a blessing for our family. This is not bragging. This is reality. This is what I was told by my boss, Bill Silversmith. I used to see him at Earl’s Restaurant a lot. We were young in those days. We both changed a lot. I’m a hastiin sani too. That means “old man.”

Boom town

Grants and Gallup were booming during the uranium mining. Lots of action going on in those days. Grants is a ghost town now.

The toxic legacy

Beta rays bounce off you. Gamma radiation goes through you. It kills your cells. It leads to cancer. Radon gas will kill you slowly. I remember this guy. That one place where I used to work, his family lived near the shafts. Not two-hundred yards away from old shafts. The families who lived there brought lumber from the mining shafts to their home. Some people have a radon exhaust shaft near their homes where the surface air goes in and the radon was pumped out. They had their sheep there. The company was planning for a shaft on the west side. They cleared the land. They were going to install a rail for about a mile-and-a-half. The company didn’t get to build that.

The wind takes the dust and people breathe it in. You cannot eat those animals out there. They drink the water. They eat the grass. Especially the cows and horses. If I had livestock, I’d herd them away and not sell them or give them to anyone. If they died, I’d get a backhoe and cover them. The dust is everywhere.

“Anyway, that was my war story.”

The pandemic is far more dangerous than anything else. Radon will slowly kill you. In this pandemic, you either live or die. Working in a disaster area like that, whether in a uranium mine or in a pandemic, you’re on a suicide mission. For what? Money? You know? Everyone works for money.

This story is a glimpse from a former uranium miner’s perspective on the Navajo Nation. Uranium mining, like many resource extraction jobs on the Navajo Nation, was ultimately not a permanent job for all Native American and other local residents. In addition, many uranium miners today suffer from the effects of inhaling dust and exposure to radiation and radon gas. On July 16, 1979, a mining dam broke near Church Rock, NM, releasing 93 million gallons of contaminated water containing mining tailings. The spill flowed through Gallup, NM in the Rio Puerco. It is viewed by many as one of the worst eco-disasters in the United States, but had received minimal media coverage at that time. Some, not all, families near the mining shafts have now moved out of their homes through relocation programs.

*Navajo Tribal Utility Authority: A Navajo Nation-owned company that provides multiple paid services that include water, electricity, natural gas, communications, wastewater, generation, and solar power.

Resources

Poison in the earth – This Navajo Times article contains interviews with former Church Rock mine employees and the Navajo locals’ experiences with living close to the mine itself.

For the Navajo Nation, Uranium Mining’s Deadly Legacy Lingers – This NPR article and three-minute audio file contains a news segment about the uranium mining industry, with interviewees that include field researcher Maria Welch, who surveys families for the Navajo Birth Cohort study and whose home was located in a uranium-contaminated area.

The Uranium Mine Industry in New Mexico – A 1977 primary source for middle school students. Doubt about the future of uranium production in the Southwest is expressed in this report.

Kerr-McGee – The Oklahoma Historical Society features a historical entry on the offshore drilling firm known as Kerr-McGee. Middle school students can read about who Robert Samuel Kerr and Dean Anderson McGee were before they became Kerr-McGee company founders.